¶ Problems We Seek To Address

Problems that Could be Solved with a New Regulatory Framework

It takes over 10 years and $2.6 billion to bring a drug to market (including failed attempts). It costs $41k per subject in Phase III clinical trials.

The high costs lead to:

¶ 1. No Data on Unpatentable Molecules

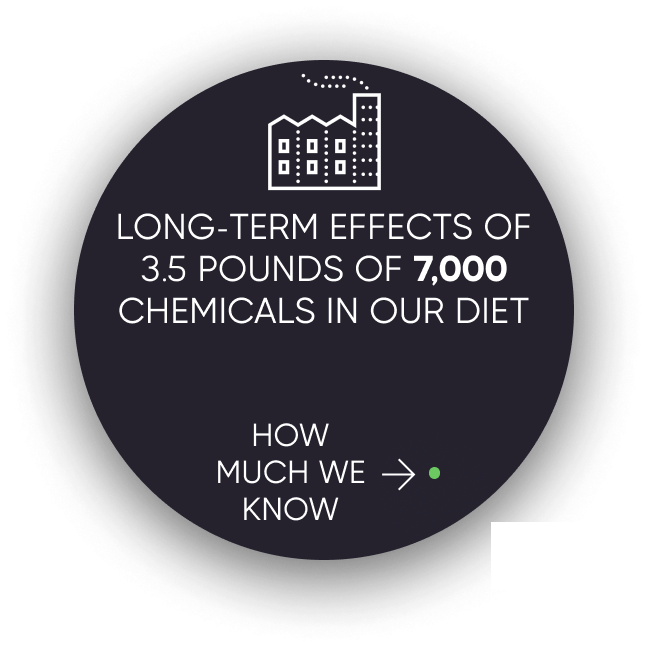

We still know next to nothing about the long-term effects of 99.9% of the 4 pounds of over 7,000 different synthetic or natural compounds. This is because there's only sufficient incentive to research patentable molecules.

¶ 2. Lack of Incentive to Discover Every Application of Off-Patent Treatments

Most of the known diseases (approximately 95%) are classified as rare diseases. Currently, a pharmaceutical company must predict particular conditions to treat before running a clinical trial. Suppose a drug is effective for other diseases after the patent expires. In that case, there isn't a financial incentive to get it approved for the different conditions.

¶ 3. No Long-Term Outcome Data

It's not financially feasible to collect a participant's data for years or decades. Thus, we don't know if the long-term effects of a drug are worse than the initial benefits.

¶ 4. Negative Results Aren't Published

Pharmaceutical companies tend to only report "positive" results. That leads to other companies wasting money repeating research on the same dead ends.

¶ 5. Trials Exclude a Vast Majority of The Population

One investigation found that only 14.5% of patients with major depressive disorder fulfilled eligibility requirements for enrollment in an antidepressant trial. Furthermore, most patient sample sizes are very small and sometimes include only 20 people.

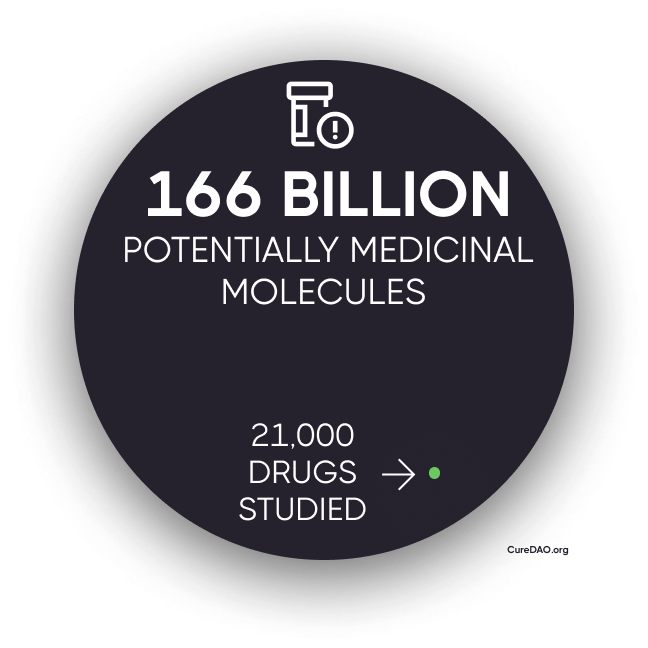

¶ 6. We Only Know 0.000000002% of What is Left to be Researched

The more research studies we read, the more we realize we don't know. Nearly every study ends with the phrase "more research is needed".

If you multiply the 166 billion molecules with drug-like properties by the 10,000 known diseases, that's 1,162,000,000,000,000 combinations. So far, we've studied 21,000 compounds. That means we only know 0.000000002% of the effects left to be discovered.

¶ 7. Bias Towards Rejecting Effective Treatments

Humans have a cognitive bias towards weighting harmful acts of commission to be worse than acts of omission even if the act of omission causes greater harm. It's seen in the trolley problem where people generally aren't willing to push a fat man in front of a train to save a family even though more lives would be saved.

Medical researcher Dr. Henry I. Miller, MS, MD described his experience working at the FDA, “In the early 1980s,” Miller wrote, “when I headed the team at the FDA that was reviewing the NDA [application] for recombinant human insulin…my supervisor refused to sign off on the approval,” despite ample evidence of the drug’s ability to safely and effectively treat patients. His supervisor rationally concluded that, if there was a death or complication due to the medication, heads would roll at the FDA—including his own. So the personal risk of approving a drug is magnitudes larger than the risk of rejecting it.

It's Impossible to Report on Deaths That Occurred Due to Unavailable Treatments

Here's a news story from the Non-Existent Times by No One Ever without a picture of all the people that die from lack of access to life-saving treatments that might have been.

This means that it's only logical for regulators to reject drug applications by default. The personal risks of approving a drug with any newsworthy side effect far outweigh the personal risk of preventing access to life-saving treatment.

Types of Error in FDA Approval Decision

| Drug Is Beneficial | Drug Is Harmful | |

|---|---|---|

| FDA Allows the Drug | Correct Decision |

|

| FDA Does Not Allow the Drug | Victims are not identifiable or acknowledged. |

Correct Decision |

¶ How a DAO Regulatory Body Could Overcome Perverse Incentives

Overcoming Cognitive Bias Against Acts of Commission

In a DAO comprised of a large number of prominent experts, no individual could be blamed or have their career destroyed for making a correct decision to save the invisible lives of the many at the risk of the lives of the few.